It was my first hike of the year. Weighed down by a few extra holiday pounds, I was fully aware of the challenge ahead—but the journey almost ended before it began. I pulled up to the small trailhead parking lot just before 9:00 a.m., and my friend was still on the road with his hazard lights blinking, hesitant to risk his loyal Camaro in the unplowed lot.

We were unfamiliar with the area and unsure of our next move, when suddenly a local rolled up and hopped out of his car to lend a hand. Quickly understanding the situation, he gestured for us to follow him back down the road, leading us to a more accessible boat dock that fed into the trail in the opposite direction we originally planned.

Little did we know, this detour was a gift from Mother Nature, ensuring we would be in the right place at the right time to witness something spectacular. We nestled our cars in and set off into the woods along the Susquehanna River.

The undulating trail had me huffing and puffing, half my brain focused on keeping my breakfast where it belonged, the other half trying to absorb the serene winter landscape, snow blanketing the forest floor under a clear January sky. “Oh my God, look! It’s a…” My head snapped up, eyes darting in all directions. And there it was. Before he could get the words out, the creature engulfed my gaze and left me in awe.

A massive bald eagle soared effortlessly among the treetops, its sharp eyes scanning the creek below. Sunlight gleamed off its frosted crown and mahogany wings. The unexpected sighting jolted us with excitement. “We basically just hit the lottery!” my friend shouted, before giving me a brief rundown of the bald eagle’s resurgence in Pennsylvania.

Comparing a bald eagle sighting to hitting the lottery is hyperbole nowadays, but several decades ago, the species was perched on the edge of extirpation. Aside from habitat destruction, bald eagles were among the most persecuted birds of the 18th and 19th centuries, as citizens adopted a kill-or-capture mindset, feeling the need to either eliminate the threat, or tame the beast.

This sentiment was influenced in part by renowned naturalists like John James Audubon, who in his 1831 Ornithological Biography proclaimed, “I grieve that it should have been selected as the Emblem of my country,” describing bald eagles as lazy, thieving, murderous birds. Many influential figures of the era held similar views, projecting human morality onto wild animals. Behaviors like scavenging and kleptoparasitism, when animals steal food from one another, were viewed with disdain, not yet recognized as essential survival strategies.

He concluded his assessment with an equally harsh quote from Benjamin Franklin: “I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character,” referencing their habit of snatching ospreys’ lunch midflight. More broadly, predatory birds were viewed as competition for valuable food sources, making them targets. This perception contributed to a steady decline in their populations.

It seemed like the bald eagle’s luck was finally starting to change in 1940 when the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act swept the nation, prohibiting any harmful interference with the misunderstood predators—including killing, capturing, and selling them, or even possessing their feathers. First-time offenders would face a potential $500 fine and up to 6 months in prison. The financial penalties have skyrocketed since the bill’s inception, with individual violators now subject to a $100,000 fine (double that for organizations), and up to one year in prison. Multiple offenses are classified as felonies and incur even harsher penalties.

Before the bald eagle could make a significant recovery, a more insidious threat emerged during World War II: the chemical DDT. This potent insecticide was praised for its effectiveness in reducing the spread of diseases like malaria and typhus. After the war, it became pervasive in agriculture, from large-scale farming operations to your average home garden.

DDT decimated several raptor populations, including the peregrine falcon, the fastest animal on Earth, and the osprey, the fishing king of the sky. The chemical worked its way up the food chain through a process known as biomagnification, where apex predators end up consuming the highest concentrations of toxic substances that seep into the water systems. High levels of DDT disrupt calcium production in these majestic birds of prey, resulting in thinner eggshells that are unfit to handle the weight of its brooding parent.

Luckily, in 1962, fellow Pennsylvanian Rachel Carson, a marine biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), published Silent Spring, exposing the pernicious effects of DDT on every living thing in an ecosystem, including humans. The book was the pivotal first step towards healing the environment from the pyrrhic consequences of chemical use.

The message finally broke through in 1972 with a nationwide ban on DDT, but the damage was profound and long-lasting. An abysmal three active nests endured into the early 1980s, all confined to a single county—down from an estimated 100 nesting pairs before the war. In 1983, the Pennsylvania Game Commission launched a bold effort to save its flying symbol of freedom: a reintroduction program supported by several organizations, including the FWS and the Richard King Mellon Foundation. Another key partnership was with the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, which boasted a healthy population of 1500 breeding pairs. Over a seven-year period, a recovery team safely collected, cared for, and released 88 juvenile Canadian eagles into Pennsylvania.

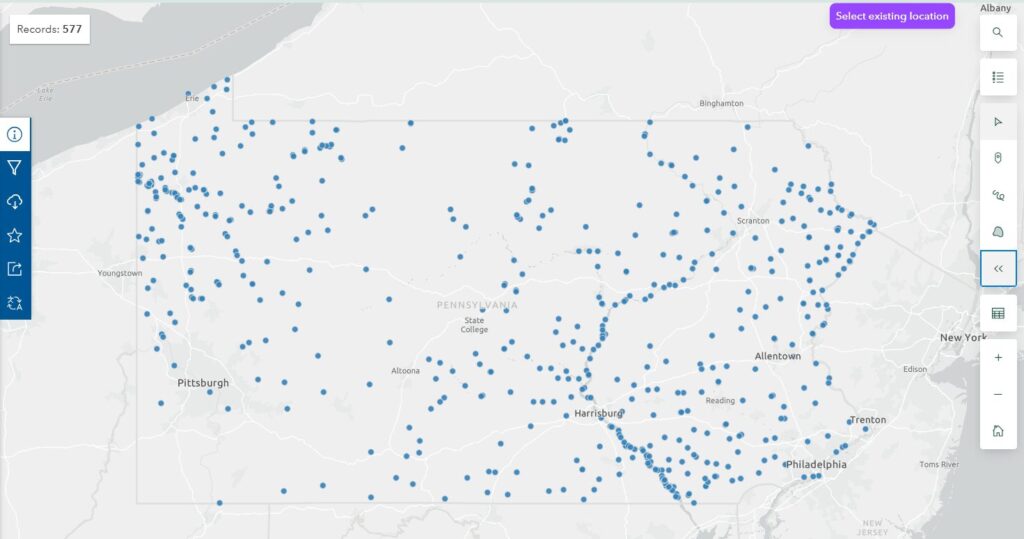

The population has continued to soar across the state over the last three decades, even surpassing pre-war levels. Close to 300 pairs were documented in 2013, and based on survey data from 2022, an interactive map on the FWS website plots out 577 intact nests scattered throughout the state. Nesting pairs sometimes build alternate nests, meaning the number of nests doesn’t directly equal the number of pairs, but the data remains impressive.

I reached out to Dr. Blake Massey, a geospatial biologist with the FWS who developed the interactive nesting maps. He’s contributed to eagle conservation research across the country, from the eastern seaboard to the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. When asked if there was something that stood out to him about the species, he thought back to a project that involved attaching GPS transmitters to adult bald eagles in Maine, tracking their whereabouts for two years.

Nearly all the birds stayed in Maine both years, willing to endure the harsh winters, but one eagle repeatedly migrated the entire length of the East Coast, traveling all the way to a spot near Orlando, Florida. Dr. Massey was struck by this exceptional adaptability—individuals from the same area choosing to take different survival paths—some hunkering down, and others embarking on a major migration.

It’s important to highlight the adaptability and perseverance of this capable creature, while recognizing that legislation and conservation efforts have been critical in restoring the population, which is flourishing. However, numerous threats still require our vigilance: vehicle collisions, lead poisoning from spent ammunition, electrocution, and human disturbance, to name a few.

When spending time in riparian forests and wetlands during prime nesting season (which varies by region), proper etiquette is crucial. Disruptive behavior around a nest can interfere with feeding, expose vulnerable hatchlings to harsh weather and predators, or startle young eaglets into a premature jump.

Some of Dr. Massey’s nesting maps display buffer zones around each site, representing tiers of urgency during nesting season. The FWS National Bald Eagle Management Guidelines outlines a 330’ critical radius that restricts all forms of visual and auditory disturbances, a 330’- 660’ secondary zone allowing for limited recreational activity and vehicle use, and a 660’- 1000’ tertiary zone permitting small construction and timber operations. Aircraft, unless specially authorized, should stay beyond 1000’, and jarringly loud activities like fireworks should be at least a half mile away. These zoning guidelines help create a balance between land use and wildlife conservation, so that we can protect eagles, and our wallets.

The resurgence of bald eagles in Pennsylvania is a story of incredible resilience, a testament to the species’ symbolism—but their story isn’t finished. Human interference will continue to shape their destiny, and with our ongoing support, the future will remain bright for our nation’s sovereign bird.